Comiskey Park’s Exploding Scoreboard Was a Spectacle Like No Other in Baseball

One of the showcases of this Chicago ballpark was a scoreboard that put on a show of its own whenever the White Sox homered.

by Rich Watson

In 1948, James Cagney made a movie called The Time of Your Life, about the customers of a saloon. Cagney’s character played a pinball machine. At one point, he hit the jackpot and the game lit up, making all kinds of noise.

Bill Veeck saw the film. He was one of baseball’s great raconteurs and iconoclasts during his four decades as an owner for three different teams, including the White Sox. He looked for innovative ways to sell the game, from night baseball to integration to wacky fan promotions and more.

Seeing Cagney with his pinball machine inspired Veeck to commission the creation of something that would enliven the experience of coming to Chicago’s Comiskey Park.

The original Comiskey Park

The park was built in 1910 by former ballplayer turned owner Charles Comiskey in Chicago’s Armour Square neighborhood, on West 35th Street. It was also called White Sox Park.

Of the Sox’ three championship titles, the only one they won during the original Comiskey Park era was in 1917. They beat the New York Giants in six games. The Sox won a hundred games that season, which remains a franchise record.

The crosstown Cubs played a World Series at Comiskey in 1918, on account of it being bigger than Wrigley Field. They lost to the Red Sox in six. In addition, Comiskey hosted three All-Star Games and a number of Negro League All-Star Games, as well as football and soccer games.

In 1937, boxer Joe Lewis began his eleven-year run as heavyweight champion with a win over James J. Braddock at Comiskey.

Great sights, all—but Veeck had a sight of a different kind to come.

The “screeching banshee”

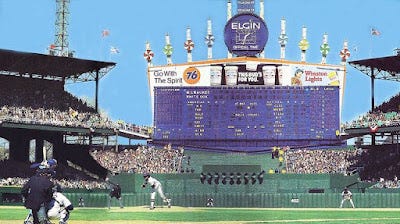

It was called the “exploding scoreboard.” It cost three hundred thousand dollars. It stood beyond the center field wall, a hundred thirty feet wide. In addition to the usual amenities, such as player lineups, an out-of-town scoreboard and a clock, ten light poles ran across the top with eight colorful pinwheels attached. Behind the scoreboard was a platform for fireworks.

When the Sox hit a home run… but that didn’t happen on April 22, 1960, the team’s home opener. Fans had to wait until May 1 to see it in action.

It was in a game against Detroit, with Jim Bunning on the mound. There was no score in the bottom of the third inning. Outfielder Al Smith was at the plate with a man on base and two out. Bunnng pitched, Smith swung, and hit a home run—and the scoreboard erupted.

The Chicago Tribune reported the scene:

Cheers of 29,586 spectators still were ringing in their ears and their eyes were half-blinded by the multicolored send-off given them by the electrical monster in center field.

Noises such as thunder and the sound of crashing trains went off. Strobe lights flashed. The pinwheels spun. Fireworks exploded in the sky above Comiskey.

Veeck’s wife Mary Frances said the whole thing “wasn’t very genteel”:

I mean, if you do something well, shouldn’t you just be modest about it? But the fans loved it, and I came to love it too. And Casey Stengel, when he managed the Yankees, had an answer for the quiet scoreboard when one of his players hit a homer: He had four or five of his men light sparklers in the dugout.

The Tribune would call the scoreboard a “screeching banshee.” Veeck discusses it in this video.

Shrinking Comiskey for more home runs

The scoreboard was used for more than Sox home runs. It celebrated the end of a long losing streak once; another time it commemorated the birth of Veeck’s daughter. As the years progressed, however, it didn’t explode as often as expected.

When Comiskey was first erected, the foul lines were 363 feet from home plate. The power alleys, left-center and right-center, were 382 feet and center field was a whopping 420 feet. By 1982, the Sox had 51 homers at home, the third-lowest total in the American League.

Thus, the decision was made to change the field’s dimensions. The result next year was 99 wins and an AL West division title under manager Tony La Russa—and more use of the exploding scoreboard. This MLB.com article details the story.

Comiskey’s demise

According to Field of Schemes, the book by Joanna Cagan and Neil deMause about the recent stadiums built from public funds, White Sox owners Jerry Reinsdorf and Eddie Einhorn, Veeck’s successors, hired an engineering firm during the eighties to see if old Comiskey could be renovated. After a battery of tests, the firm concluded it should be torn down and replaced with a new stadium, across the street from Comiskey.

The owners threatened to move the Sox to St. Petersburg, Florida if Chicago didn’t build them a new park. Despite a grassroots resistance movement, which included the black residents of private homes threatened with demolition via claims of eminent domain, the deal was made. From Field of Schemes:

The intensive lobbying of team officials and major league baseball higher-ups, combined with high-pressure tactics to prove [the Sox’] threat to yank the team was legitimate, proved too much for the Illinois State Legislature. In a midnight session on June 30, 1988, the body approved construction of a new stadium, with $150 million coming from state bonds and the rest from a two percent hotel tax. (In fact, it was an after-midnight session, as Governor Jim Thompson had the clock turned off at 11:59 to avoid hitting a midnight deadline.)

The Sox played their last game at Comiskey on September 30, 1990, a 2-1 win over Seattle. The old ballpark was torn down the next year.

The last part to go was the scoreboard. The new ballpark, Guaranteed Rate Field—originally christened Comiskey Park—has a new version of the scoreboard, with only seven light poles. It also shoots off fireworks.

—————————

Have you ever gone to Comiskey Park and seen the scoreboard light up for a home run?