Connie Mack Stadium and Its Remarkable Architecture

Baseball in Philadelphia used to be played in a virtual palace.

by Rich Watson

During the early twentieth century, the Philadelphia Athletics were the dominant team in the brand new American League. This meant they were popular—to the point where fans had to be turned away from tiny Columbia Park.

Team president Ben Shibe eyed a square block of land on Lehigh Avenue between 20th and 21st Streets. It was part of an underdeveloped neighborhood, with trolley cars and railroad stations, but also containing bluffs and gullies where live animals roamed. A smallpox hospital was there too, but the city was about to shut it down.

Shibe quietly bought up the land beginning in 1907, with the intent to build a new, bigger ballpark on the site. Two years later, what he and the A’s got was nothing less than a cathedral to baseball.

William Steele and Sons had the plan for Shibe Park

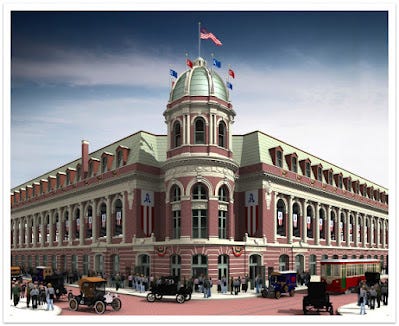

Shibe called the finished product a place “for the masses as well as the classes.” The Philadelphia Public Ledger dubbed it “a palace for fans, the most beautiful and capacious baseball structure in the world.” In future years, Hall of Famer Richie Ashburn said “it had a feeling and a heartbeat, a personality that was all baseball.”

It was the facility originally called Shibe Park, later christened Connie Mack Stadium, designed by the architectural firm of William Steele and Sons.

Founded in the late nineteenth century, they had built Philly’s first skyscraper, the Witherspoon Building, in 1895. They went on to construct, among other places:

the Terminal Commerce Building, on North Broad Street,

the Harris Building, on Market Street, and

Snellenburg’s Clothing Factory, also on North Broad.

These and other Steele buildings are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Arches, friezes, cartouches, and a cupola

Shibe Park was made from steel and reinforced concrete, a first in Major League Baseball. The original capacity was 23,000 (as opposed to Columbia Park’s 13,600). The foul lines were 360 feet (left) and 340 feet (right), with the center field corner 515 feet away from home plate. Sod from Columbia Park was used.

The French Renaissance style of the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries inspired Steele’s plan for the facade, which included arches, vaultings and pilasters. The ballpark resembled a museum or a palace but its decorations were baseball and A’s-themed: friezes and casts of balls, bats, catcher masks, and more, on red brick and terra cotta grandstand walls. The entrances had cartouches above them with A’s logos. A mansard roof with dormer windows adorned the upper deck.

In the southwest corner stood a tower for the main entrance lobby and administrative offices above, crowned by a cupola, a dome-like structure.

On Opening Day, April 12, 1909, not only did thirty thousand gain admittance, another fifteen thousand were turned away. The A’s beat Boston 8-1.

Athletics managerial legend Connie Mack

The A’s first manager, beginning in 1901, was a man born Cornelius McGillicuddy, but known to all as Connie Mack. His records for games managed, wins, and losses, still stand today. The former big-league catcher won nine American League pennants and five World Series with the A’s and retired at the age of eighty-seven.

He was also part owner with Shibe. Busts of both men hung over the 21st Street and Lehigh Avenue entrances. Shibe died in 1936 and Mack took over the franchise a year later. By 1941 he had installed not only lights for night games but a bigger scoreboard too. He also expanded capacity to over thirty-three thousand.

Mack retired in 1950. Shibe Park was renamed for him in 1953, three years before his death. A statue of him resides near Citizens Bank Park, the Phillies’ current home.

The 20th Street neighborhood “bleachers”

Because the A’s were so popular, fans who couldn’t make it to Shibe Park found other ways to see the game. The houses on 20th Street were high enough to see games on the roofs, looking out from over the low right field wall. Photos of the neighborhood from the 1910s depict fans jamming the streets below and the roofs above. The homeowners charged for admission and even sold hot dogs.

During the thirties and the Depression, when the A’s were strapped financially, they raised the outfield fence to cut off the view. Thus no more free games for those on 20th Street, who referred to the obstruction as a “spite fence.” The players weren’t too thrilled with it either; for the left-handed ones, it meant fewer home runs. Plus the corrugated metal of the fence made playing balls hit off of it tricky.

Here’s an article about the 20th Street neighborhood and the A’s “spite fence.”

The Phillies as co-tenants

The Phillies of the National League played in the nearby Baker Bowl, five block west from Shibe Park. When the right field grandstand collapsed in 1926, the team had to use their neighbors’ ballpark the next year. By 1938, the move was permanent when it became clear the Phillies couldn’t use the Baker Bowl any longer.

They played at Connie Mack Stadium until 1970. While there, they won the pennant in 1950 before losing to the Yankees in the World Series.

The Athletics leave Philadelphia and other events

After Mack’s retirement, the Mack and Shibe families squabbled over control of the team, but bad business decisions plus declining attendance figures led to financial trouble for the franchise. Chicago businessman Arnold Johnson bought the A’s and moved them to Kansas City in 1954, where he owned the ballpark that would become Municipal Stadium.

The Phillies remained in Connie Mack Stadium, now owned by DuPont heir Bob Carpenter, but his improvements didn’t help attendance. A lack of sufficient parking space, plus a declining neighborhood, contributed to the stadium’s troubles as well.

Carpenter sold the stadium in 1961. Subsequent plans to save the ballpark came to nothing. The final game, a 2-1 Phillies win over Montreal, was played on October 1, 1970.

By 1971, the Phillies moved into brand-new Veterans Stadium. On August 20, 1971, as Connie Mack Stadium was rededicated at the Vet, a fire started by two young stepbrothers broke out. What remained of the ballpark was deemed unsalvageable and it was razed.

The corner tower and cupola were the last pieces to go. A church now stands on the original site today.

Connie Mack Stadium’s legacy lives, after a fashion. Citizens Bank Park contains a concourse named for Phillies legend Richie Ashburn. Atop its concession area are the Rooftop Bleachers, inspired by the old 20th Street rooftop seats.

————————

Did you ever see a game at Connie Mack Stadium?