The “Other” Wrigley Field Was the Setting For a “Twilight Zone” Episode

This West Coast version of Wrigley Field only lasted one year in MLB, but it was often used for TV and film.

by Rich Watson

This post is for the Favourite TV Show Episode Blogathon, another long-running blog event—this year marks the eighth annual edition. I think the premise is self-explanatory. At the end I’ll tell you where and when you can read more entries in this vein.

————————

Chicago’s Wrigley Field, the home of the Cubs for over a century, is one of Major League Baseball’s oldest and greatest ballparks. Named for owner William Wrigley, the chewing gum manufacturer, he also owned the Cubs’ old farm team, the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League.

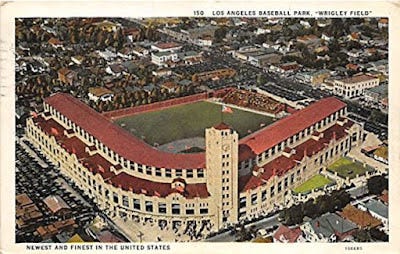

In 1925, he commissioned a new ballpark for the Angels and moved them there, on 425 East 42nd Place. It was called Wrigley Field before the one in Chicago. It also received lights long before its namesake.

Future Dodger and Cub turned actor—not to mention an NBA player—Chuck Connors played in Wrigley Field West. (I’m calling it that to distinguish it from the Chicago one.) Here’s an article about his sports career, including the story of how he settled a contract dispute between the Dodgers and two of their superstars.

The Angels had won six PCL championships before moving to their new ballpark, and would win five more at Wrigley. Even in those early years, though, it was clear the new park could be used for another purpose: making movies.

Wrigley Field West: a pawn in the L.A. baseball shuffle

Wrigley also hosted the Angels’ rivals, the Hollywood Stars, from 1926-35, plus a brief return in 1938. The Stars won back-to-back PCL titles in 1929-30 while playing in Wrigley. Here’s a more detailed history of the Stars in their own ballpark.

In 1957, Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley bought Wrigley Field West and the Angels before transplanting his team from Brooklyn. The next year, the Angels shifted to Spokane, Washington.

The now-Los Angeles Dodgers played, not at Wrigley but at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum and then the new Dodger Stadium. Their “LA” cap logo comes from the minor league Angels.

L.A. received a major league Angels team in the 1961 expansion. They spent one year at Wrigley before heading to Dodger Stadium and then to nearby Anaheim. Yes, these teams did a lot of moving.

Here’s some rare color footage of Wrigley, featuring Negro League great Satchel Paige in a 1948 exhibition game.

Wrigley in the movies and TV

Wrigley’s movie debut came in 1927 with the Babe Ruth silent film Babe Comes Home, the only one of the ten movies he made where he didn’t play “Babe Ruth.” A lost film, it had music and sound effects but no dialogue. Full sound in motion pictures, including dialogue, came later that year with The Jazz Singer.

Among the other films shot at Wrigley include The Winning Team, Damn Yankees, Meet John Doe, the noir film Armored Car Robbery, and the Lou Gehrig biopic Pride of the Yankees, also featuring Ruth. This blog has more detail about Wrigley substituting for Yankee Stadium in that movie.

Home Run Derby was a TV show from 1960 shot at Wrigley. Players such as Hank Aaron, Mickey Mantle, Willie Mays, Frank Robinson, Duke Snider and more competed in a home run-hitting contest. This was years before the All-Star Game carried on the tradition.

Also that year, Wrigley was used for a comedic episode of one of television’s greatest anthology series.

Pitching in The Twilight Zone

For five seasons in the late fifties-to-early sixties, creator and host Rod Serling took viewers on a journey into another dimension, not of sight and sound, but of mind. The Twilight Zone stories generally had a supernatural bent, but were done in various genres: suspense, sci-fi, fantasy, drama, horror, Western—and the occasional comedy.

The first-season episode “The Mighty Casey,” written by Serling and directed by Robert Parrish and Alvin Ganzer, was the only baseball-related episode (but not the only sports-related one). It starred future Emmy-winner Jack Warden.

The Hoboken Zephyrs, perennial doormats, get a break when the manager discovers pitching phenom Casey (played by Robert Sorrells), an artificial intelligence—a robot. Complications arise when Casey’s true nature is uncovered.

Serling wanted to use the Dodgers as his lovable losers, but they had just won the previous year’s World Series. Similar to when the Farrelly Brothers had to reshoot the ending of Fever Pitch, Serling changed his story.

The crowd footage in the episode was taken from the Polo Grounds and Fenway Park.

“The Mighty Casey:” a troubled production for a light episode

“Casey” originally starred Paul Douglas, a veteran actor who had appeared in, among other pictures, the popular baseball films Angels in the Outfield and It Happens Every Spring. McGarry, the Zephyrs’ manager, was a role written for him. (Douglas was also slated to appear in future Best Picture Oscar-winner The Apartment.) Ganzer was the initial director.

Principal photography on “Casey” wrapped in September 1959. No one knew, however, that during the production, Douglas had suffered a coronary that affected his performance. On the morning of the eleventh, he rose from his bed, had a heart attack and died.

Serling had to replace Douglas with Warden and to reshoot the episode with money out of his own pocket. (The Apartment production also had to recast.) Ganzer was unavailable, so Parrish stepped in as director; both men were credited.

The only bit of footage with Douglas remaining in the final cut was the last shot: an overhead, faraway angle of Douglas on the Wrigley Field turf, with his back to the camera.

What constitutes humanity?

“Casey” ponders what makes a human a human. The league wants to disqualify Casey from the Zephyrs because as a robot, he runs on circuits and gears, not a human heart. McGarry argues he looks like a human, and that should be enough.

It’s a debate that’s given surface attention in the teleplay—and indeed, throughout cinematic history to this point, it wasn’t explored much. As AI such as Alexa and Siri become more commonplace in the twenty-first century, though, it’s worth further exploration.

Pop culture certainly has. In the book Is Data Human? The Metaphysics of Star Trek by Richard Hanley, the author examines how to approach the question of sentience in an AI, using the Star Trek: The Next Generation character Data as a template:

…In addition to asking, Given what we know about Data, what is the reasonable thing to conclude about whether or not Data is a person? we shall also ask, Is artificial personhood even possible? If the answer to the second question is negative, then of course Data is not a person. But note that even if the answer to the first question is that we ought to consider Data a person, Data is after all fictional and might well be an impossible construct of the imagination.

Casey’s creator, Dr. Stillman, claims he can supply Casey with a heart. Stillman doesn’t specify whether it would be real or artificial, but the league commissioner says it would do to qualify Casey as a human.

Stillman performs some manner of procedure off-camera. The next time we see Casey, he has something in his chest that thumps like a heart and he acts more human-like. It’s a solution of which the Wizard of Oz and the Tin Man would’ve approved.

Like when Data got an emotion chip installed, though, the solution for Casey isn’t that simple. With a heart, he’s less effective as a pitcher. He’s too emotional!

There may be something to this idea, if you consider how a pitcher like Bob Gibson used intimidation as a weapon against his opponents. As to whether or not a heart alone makes Casey, “an impossible construct of the imagination,” human… let’s just say the umpires are still conferring.

Bottom line

As a comedy episode, I found “Casey” tepid. Serling’s strengths as a writer were many, but comedy was not one of them. As a piece of sci-fi, writing this post has given me a new appreciation for it—not that I would place it among the best TZ episodes. I imagine this looked different to a 1960 audience.

As for Wrigley Field West…

Once the major-league Angels moved to Anaheim, the ballpark had little purpose for anything other than concerts and events and the occasional soccer match. Wrigley Field was demolished in 1969 and replaced with a park, a mental health center and a parking lot.

————————

Other entries in the Eighth Annual Favourite TV Show Episode Blogathon can be found at the website A Shroud of Thoughts on March 18-20.