The Polo Grounds Went Through Four Incarnations (and a Weird Shape) to Become a Legend

The Manhattan stadium seemed ill-suited for baseball, yet it was home to some of baseball’s best and worst moments.

by Rich Watson

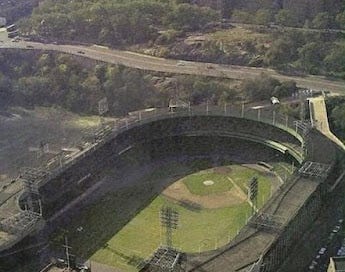

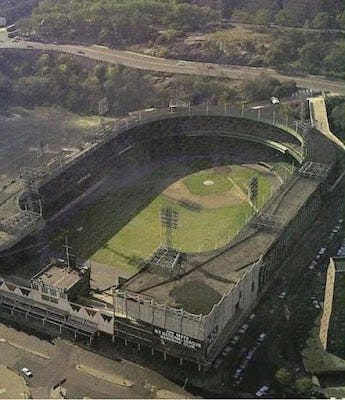

Its shape resembled a giant bathtub. The foul lines were so short they were more appropriate for a high school baseball game, and its center field could’ve been reached if one used a trebuchet in place of a bat. Not only did one of the winningest baseball teams play there, though, a number of the game’s most memorable events occurred at this place.

New York City’s Polo Grounds was unique among ballparks. Within it, the Giants dominated for years before the cross-town Yankees became a powerhouse. After the Giants left, the Mets moved in and established a new standard for futility.

And no one actually played polo there.

The Polo Grounds: versions 1-4

The first venue known as the Polo Grounds, which did have polo (among other things), was on 110th Street in Manhattan, across from Central Park, in 1880. A Mets team, called the Metropolitans, played there with the Gothams, the forerunners to the Giants.

In 1886 the Mets moved to Staten Island. The Gothams had become the Giants.

Plans to restructure the city streets forced the Giants to move, to Jersey City, Staten Island, and finally to the area known best today: 155th Street and Eighth Avenue (a.k.a. Frederick Douglass Boulevard) during the 1889 season. This was Polo Grounds II.

The site was next to a promontory known as Coogan’s Bluff, named for a real estate developer. Fans would watch games from this point.

To the north and next door, in a place called Brotherhood Park, was a Giants team from a rival league. In 1890 this league merged with the National League and the NL Giants moved into the park. This became Polo Grounds III.

In 1911 a fire destroyed the mostly wooden park. Giant owner John T. Brush had a concrete-and-steel replacement built in months. This was Polo Grounds IV, the most familiar version.

The Yankees were co-tenants with the Giants beginning in 1913. After the 1922 season, they moved across the Harlem River to the Bronx to build Yankee Stadium. The Giants countered with expanded seating, from 34,000 to 55,000.

The highlights in Polo Grounds history are many: a twenty-six game winning streak in 1916, two All-Star Games, the emergence of Willie Mays, seventeen pennants and five World Series championships.

Three moments stand out.

“The Boner”

In 1908, the Giants struggled through a year-long battle with the Pirates and Cubs. On September 23, the Giants played the Cubs at the Polo Grounds. When the regular first baseman was hurt, rookie Fred Merkle started instead.

The score was 1-1 in the bottom of the ninth, with the winning run at third and Merkle at first. The next batter hit a single. The game appeared over; the Giant fans swarmed the field and Merkle started for the dugout.

Then, the second baseman caught the relay throw from center, stepped on the bag and Merkle was ruled out on a force play. The umpires nullified the winning run and the game was called on account of darkness.

The Cubs won the replayed game the next day and went on to win the pennant. History immortalized the baserunning gaffe as “Merkle’s Boner.”

“The Shot”

Left field was a mere 279 feet from home. In 1951, Mays’s rookie season, the Giants and Dodgers finished in a tie at 96-58. They went to a best-of-three playoff series. Each team won a game.

In Game 3 at the Polo Grounds, a contest broadcast nationally on radio (including Armed Forces Radio), the score was 4-1 Dodgers in the bottom of the ninth.

The Giants rallied for a run, then, with one out and two on, Bobby Thomson, the winning run, came to the plate. Dodger pitcher Ralph Branca entered the game in relief. Mays was on deck.

Thomson knocked the 0-1 pitch into the left field stands for a home run and the Giants won the pennant. The press called it “The Shot Heard ‘Round the World.”

“The Catch”

Center field was a whopping 483 feet from home plate. In 1954, the Giants played the Indians in the World Series.

In Game 1, the score was tied 2-2 in the top of the eighth inning. Cleveland’s Vic Wertz, on a 2-1 pitch with runners on first and second, hit a long fly ball to center. Mays ran hard with his back to the plate.

Just as he reached the warning track—again, with his back to the plate—he reached out and made a stunning over-the-shoulder catch (and had the presence of mind to make a relay throw to the infield).

The Giants went on to win the game and the Series, in part because of Mays and “The Catch.”

Tainted legacy

The glove Mays used to make The Catch is at Cooperstown. The 1908 season, including Merkel’s Boner, is the subject of a recent book.

The moment of Thomson’s homer, however, has been marred by a startling revelation: the Giants stole signs during that 1951 season.

Until the day he died in 2010, Thomson insisted he didn’t steal a sign at the moment he hit the home run. MLB had no explicit rule on the books against sign-stealing in 1951. They did by 1961.

The Giants head west for San Francisco

The Polo Grounds looked ragged in the fifties, and after 1954, so did the Giants. Attendance suffered. The surrounding neighborhood deteriorated. Parking was limited; fans who came by subway used a stairway on Coogan’s Bluff to reach the ballpark.

Owner Horace Stoneham contemplated a new stadium. Minneapolis was an option; that was the home of the Giants’ top farm team. Sharing Yankee Stadium was another. Then San Francisco made an offer, around the same time the Dodgers itched to leave Ebbets Field for Los Angeles.

MLB wanted two teams in the new frontier of California. They wouldn’t allow the Dodgers to move unless it was with a second team, so owner Walter O’Malley convinced Stoneham to come with him.

According to the book about the Giants’ and Dodgers’ New York exodus, After Many a Summer by Robert E. Murphy, Wall Street Journal writer Thomas O’Toole crashed an August 1957 stockholders meeting and relayed this account of Stoneham selling them on the prospect of moving west:

“If we don’t get out of New York,” [O’Toole] quoted Stoneham as telling his investors, “we’re going to lose money and all the good cities will be gone.”

The owner expected to receive a formal letter of intent from Frisco within a week and promised that “When we go to San Francisco, we’ll make money. I can almost guarantee a net profit of $200,000 to $300,000 a year”…. [H]e said he expected that his closed circuit [TV] contracts “will double our present radio and television income.”…

“As Mr. Stoneham ticked off the advantages of moving to San Francisco,” wrote O’Toole, “there was a perceptible change of mood among stockholders. Out of the early gloom came some lively, good-natured banter.”

Stoneham also said he wasn’t concerned about earthquakes. Obviously he didn’t have a crystal ball.

He did, however, convince the Giant braintrust. The team moved to San Francisco in time for the 1958 season.

But that wasn’t the end of baseball at the Polo Grounds…

Meet the Mets!

The possibility of a third major league in 1959 led to a wave of expansion by MLB to quell the uprising. One of the new teams would be in New York, to fill the void left by the Giants’ and Dodgers’ departure. That team was the Mets (unconnected to the nineteenth century version), who wore Giant orange and Dodger blue.

A new stadium was in the works, but until then the new team would inhabit the Polo Grounds. Among the initial roster included former Giants and Dodgers; manager Casey Stengel himself was a former Giant and Dodger from the early twentieth century.

Expansion teams tend to begin poorly, but the Mets redefined “poor” in 1962: their 40-120 record ranks among the worst seasons in professional sports.

Despite that, fans perceived the Mets as fun. A combination of the zeitgeist of the times, joy at having an NL team in New York again, a backlash against the staid, more traditional ways of the Yankees and the antics of lovable curmudgeon Stengel made the Mets’ ineptitude not only tolerable, but cheerful.

The Mets stayed at the Polo Grounds for two years, until they moved into the new Shea Stadium in Queens in 1964.

Pro and college football at the Polo Grounds

The football Giants, one of the original NFL teams from 1925, began play at the Polo Grounds. They won three championships during their stay before migrating to Yankee Stadium in 1956.

In 1960 came the rival American Football League, and a new team, the Titans. They stayed in the stadium until 1963, then joined the Mets at Shea as the Jets.

College football contests at the Polo Grounds date back to Columbia University games at 110th Street. The teams for Army and Notre Dame played some games at Polo Grounds IV.

Fordham, Vince Lombardi’s alma mater, played there from the 1920s to the 50s. Lombardi was an assistant coach for both Fordham and the Giants while both teams played at the stadium. Baseball Giants Hall of Famer Frankie Frisch went to Fordham.

Boxing, soccer, even midget car racing were among the alternative sports at the Polo Grounds.

The Polo Grounds’ demise

New York used eminent domain law to claim the Polo Grounds land in 1961. Three years later, the stadium was demolished. A housing project stands there now.

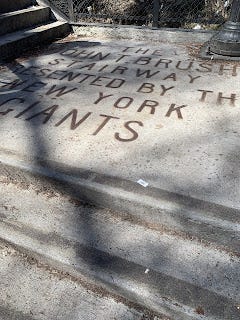

The only remnant from that era is the staircase on the bluff, named for former Giants owner Brush, who built Polo Grounds IV:

Though the Giants’ legacy in New York has often been overshadowed by that of the Dodgers, they’re still well remembered.

A Giants Preservation Society exists. Last year, the seventieth anniversary of the Shot Heard ‘Round the World, they gathered at the former site of the Polo Grounds to remember the stadium and the team that once dominated the National League like few others.

———————

Do you know someone who went to the Polo Grounds?