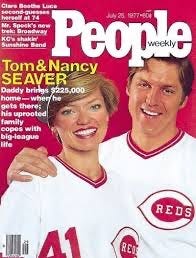

When Tom Seaver Was Traded, a Poison Pen Didn’t Keep Him and His Wife Down

A newspaper columnist libeled them, but they got the last laugh.

by Rich Watson

Tom Seaver was the lynchpin of the astonishingly successful 1969 Mets, an expansion team that went from cellar-dwelling losers to World Series champions in seven years. The Mets won a second National League pennant in 1973. Seaver and his wife Nancy were the toast of New York.

In 1977, contract renegotiations between Seaver and the Mets broke down. A newspaper column by a firebrand sportswriter made matters worse by implicating Nancy as a factor in the breakdown.

The next day Seaver had been traded.

Tom Terrific turned the Mets around

The Mets were born in 1962, after the Dodgers and Giants left New York for California. They lost one hundred twenty games in their debut season and were infamous as a notoriously awful team for years.

Tom and Nancy had been married since 1966. They met in high school and dated in college. Their oldest daughter Sarah, was born in 1970, followed by Anne in 1975. In later years, the Seavers would open a vineyard in California with their own vintage.

In 1967, Seaver joined the major leagues with the Mets. He won sixteen games and made the All-Star team. From then on, the Mets, under manager Gil Hodges, reflected a new attitude that came with increased confidence, better players, and an expectation of winning.

In 1969, Seaver went 25-7 with a 2.21 earned run average and won the Cy Young Award, baseball’s most coveted honor for pitchers—the first of three he would win, all as a Met.

Despite this, he craved greater job security.

The dawn of free agency in baseball

After decades of struggle by the ballplayers to earn a fair wage from management, including a lawsuit in 1970 by Cardinals outfielder Curt Flood, free agency blossomed in the mid-seventies.

Pitchers like Catfish Hunter and Andy Messersmith, among other ballplayers (some of whom had lesser stats than Seaver) were signing million-dollar contracts, to the excitement of some owners and the chagrin of others.

Mets chairman M. Donald Grant was against free agency. The team had struggled in the years after their pennant win in 1973. Seaver had publicly said Grant was unwilling to cough up the dough needed to make the Mets a contender again, unlike their cross-town rivals, the Yankees.

Owner Lorinda de Roulet and general manager Joe McDonald worked with Seaver on a three-year extension of the contract to which he agreed a year ago. By mid-June 1977 he was on the verge of signing the extension.

Then came a certain newspaper article.

Dick Young twists the knife with his column

Dick Young was the pioneering Daily News sports journalist who had a reputation for bluntness and confrontation. Current News sports writer Bill Madden, author of Tom Seaver: A Terrific Life, described Young this way two years ago:

...Young was not a wordsmith in the mold of Red Smith—he despised flowery prose—but no one was better or more clever at turning a phrase in the leads to his game stories and columns. When he hired me, Young had these words of advice: “Don’t try to be a [bleeping] Hemingway. You’re a newspaperman. Don’t ever forget that. Talk to your readers. Always try to tell ‘em something they don’t know.”

Seaver was part of the new wave of professional athletes unafraid to speak out on certain issues, such as labor-management relations.

This rubbed Young the wrong way, and in print, he took Grant’s side in contract negotiations with Seaver. It should also be noted that Young’s son-in-law worked in the Met front office at the time, but Young’s stance was characteristic.

On June 15, 1977, the day of the trade deadline, Young wrote a piece, widely believed to be planted by Grant, in which Young compared Seaver to former teammate Nolan Ryan, who had recently gotten a raise:

...Nolan Ryan is getting more now than Seaver, and that galls Tom because Nancy Seaver and Ruth Ryan are very friendly and Tom Seaver long has treated Nolan Ryan like a little brother.

Seaver demands to leave Mets

The Mets were in Atlanta at the time. When Seaver heard about the column, he immediately called McDonald and insisted on a trade.

By the end of the deadline, he was sent to Cincinnati for four players whose combined impact never matched that of Seaver.

“Young could call me an ingrate, a headache for Grant, anything he wanted,” said Seaver to the New York Post. “An attack on my family was something I couldn’t take.”

Young’s combative prose rarely mellowed in subsequent years, not even after a move to the Post in the eighties. When he died in 1987, the New York Times called him “the epitome of the brash, unyielding yet sentimental Damon Runyon sportswriter.” Young is in the writer’s wing of the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Seaver’s revenge as a Red

As a Red, Seaver shut out Montreal in his debut and kept Cincinnati in contention against the Dodgers. Then came Seaver’s first appearance against the Mets, in a game on August 21 at Shea Stadium.

A crowd of 46,265 came to cheer Seaver and boo the Mets. He hit a double, scored two runs and struck out eleven as the Reds trounced New York 5-1.

The Reds ended the 1977 campaign in second place with eighty-eight wins while the Mets finished last with ninety-eight losses.

Nancy fights for Tom’s legacy

Seaver went on to a first-ballot Hall of Fame career, with 311 wins and 3,640 strikeouts before his death last year.

In 2016, Nancy pointed out how current Met management had bucked a trend among major league teams by not honoring her husband with a statue. The News quoted her as calling the omission “ridiculous.”

“I’m embarrassed for [the Mets]. I really am,” she also said. “They should have a statue for all those numbers they have retired on their wall—Seaver, Gil Hodges, [catcher] Mike Piazza.”

During the 2019 celebration of the 1969 team at CitiField, the Mets not only officially renamed their stadium address 41 Seaver Way, they announced a Seaver statue was in the works. It is expected to unveil this season.

Hopefully Nancy will be there.

——————

Did you ever see Tom Seaver play?