When Wolfman Jack Was a Mystery Man on Mexican Radio

America first clapped for the Wolfman when he was broadcast from south of the border.

by Rich Watson

At the height of his fame, Wolfman Jack was better known as a TV star than a radio deejay. He hosted the music TV show Midnight Special. He popped up in shows and movies from time to time.

As a deejay, his identity was more ambiguous, but it wasn’t hard to find him. His show was on a Mexican radio station whose reach was far and wide.

Wolfman Jack’s inspirations

Long before the Wolfman first howled, he was simply Robert Smith, a technical high school graduate from Brooklyn. Like many people growing up in the fifties, he discovered early rock and roll through rhythm and blues music on the radio.

One of the most important deejays of this period, perhaps the most important, was Alan Freed. During his stint on Cleveland’s WJW as “Moondog” (named for an R&B record), he became known not only for playing R&B on a regular basis, but for uniting black and white audiences under the rock and roll banner. Tapes of his show eventually played on New York radio. In 1954, he moved to New York himself.

Other deejays spread the rock and roll sound. In Nashville, John Richbourg, known as John R on WLAC, went from newscaster to disc jockey. In Philadelphia, it was Jocko Henderson, talking jive on WHAT and WDAS. In New York, it was Tommy Smalls, a.k.a. “Dr. Jive,” on WWRL.

All these early rock jocks helped shape Smith’s sound as a deejay, particularly Freed.

Smith called himself Daddy Jules, and later, Big Smith, on radio stations in Virginia and Louisiana before taking on the moniker Wolfman Jack. It was inspired not only by Freed’s Moondog nickname, but by Smith’s love of horror movies.

It was as the Wolfman that he came to XERF in 1962, a Mexican station known as a “border blaster.”

“Border blasters” and XERF

Border-blaster radio stations target other countries. The phrase is associated with Mexican stations, but it can also apply to Canadian ones and even some European ones.

Mexican border-blasters had powerful signals: fifty thousand watts at the low end. The first border-blaster, XERA, had as much as one hundred fifty thousand watts. In addition to music considered left of center, they were full of hucksters selling everything from religion to insurance to fortune telling.

XERF operated out of Ciudad Acuña, Coahuila, Mexico beginning in 1947. It was powerful enough—two hundred fifty thousand watts—to be heard in New York. This was how the Wolfman discovered it.

In the fifties, XERF played honky tonk music. This attracted early country music greats, from Hank Williams to Johnny Cash, to promote their songs. Record label bigwigs, though, saw the emerging rock sound as more commercial.

Then the Wolfman came along, a proponent of rock and roll. And XERF’s fortunes improved.

“You gonna dig him till the day you die”

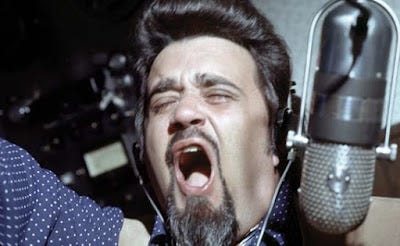

To modern ears, Wolfman sounds very different. Not only did he talk over records, sometimes he sang along with them and used funny sound effects. He flirted shamelessly with female callers. His jive patter sounded like another language. But his enthusiasm for rock and roll was clear.

He pitched a variety of bizarre products: dubious pharmaceuticals, dog food, even baby chicks.

Wolfman’s success attracted the attention of crooks and crooked government officials, to the point where he needed his own security. A U.S. communications act required him to live in Texas but broadcast in Mexico.

In the wake of a conflict between armed men and Mexican authorities at XERF, Wolfman moved to Tijuana’s XERB in 1965. His show could be heard, among other places, in Los Angeles. His show, and his legend, grew.

Who is the Wolfman?

When the Wolfman appeared in public, he never looked quite the same every time. He still wasn’t sure what he should look like, so he’d wear wigs, combed his hair different ways, applied makeup, etc.

An air of mystery surrounded him as a result. The book Everybody Had an Ocean: Music and Mayhem in 1960s Los Angeles by William McKeen describes his persona this way:

He was part of our folklore, as mysterious as the Yeti. Seeing him a few years later in American Graffiti was a fulfillment of that image we all had of the renegade disc jockey. When he later went mainstream and was all over television—hosting The Midnight Special and doing commercials, he lost his air of mystery.

Wolfman’s appearance in the 1973 George Lucas film American Graffiti cashed in on that mystery-man image even as it shattered it. He had previously been in a Russ Meyer film called The Seven Minutes two years earlier, but Graffiti was a much bigger hit, and led to bigger things.

But that is another story.

@byrichwatson

———————

Did you listen to Wolfman Jack?